By Emily Shull

By Emily Shull

In January 2016 I visited the home of a modern saint and the hero of El Salvador, Oscar Romero. It was an unforgettable experience to walk into his small house, to see the church where he was killed, and to meet those who remember him.

Oscar Romero was born in 1917. He was part of a large poor family, but he was bright and at 14 decided that he wanted to become a priest. He was sent to Rome to study because of his impressive work as young seminarian and was ordained at the age of 25. He was leading a relatively quiet life as a priest, but out of concern for poor farmers who might not feel welcome at church, he convinced local radio stations to broadcast his Sunday homilies. He was ordained a bishop in 1970. He was considered conservative and traditional by his follow Salvadoran bishops, discouraging groups who were pushing for political change because he feared the unrest it might cause.

In February 1977, Romero was made Archbishop of San Salvador and one month later his good friend Fr. Rutilio Grande was killed with two of his companions at the orders of a wealthy landowner allied with the military forces. Fr. Grande had been ministering to poor communities near his hometown. His message was a simple one; it is not God’s will for you to be poor and for your children to be hungry. In the ‘70s, 1 percent of El Salvador’s population controlled virtually all agriculture and industries. In rural communities, nearly half of children did not live to the age of 5. Work was scarce and paid very little. Romero presided at the funeral of Fr. Grande and met the people he championed. He was forever changed by sharing in their grief and love for a great man. He began to speak for the poor in his homilies, which were still being broadcast over the radio. He became the voice that told the marginalized of El Salvador of God’s love and God’s desire that their suffering would end.

Left: The Divine Providence Chapel in San Salvador where St. Romero was assassinated.

Unrest was growing in El Salvador. Open violence toward demonstrators, not just rebels, carried out by the Salvadoran military was becoming common as were the “disappeared.” Families began to approach Romero looking for loved ones who they feared had been captured or killed. Romero refused to attend any official government event and kept speaking out. By March of 1980 he openly pleaded with the military, government, and even individual soldiers to end the brutal violence. This violence was largely inflicted on the defenseless in an effort to control the people through fear. Oscar Romero was killed while saying Mass at the chapel only steps from his home on March 24, 1980. Romero had appealed directly to President Carter, but the U.S. would continue providing financial support to the military of El Salvador (the rate would increase under the Reagan administration). The U.S. feared that the leftist rebels would become allied with Communist powers in the region. Romero was unable to stop the civil war that would continue between the military and the leftist FMLN rebels for 12 more years. In a country of 5.5 million, 75,000 were killed, 1 million fled, and 1 million more became internally displaced. Of those who died, estimates say at least 30,000 were not part of the FMLN or the military.

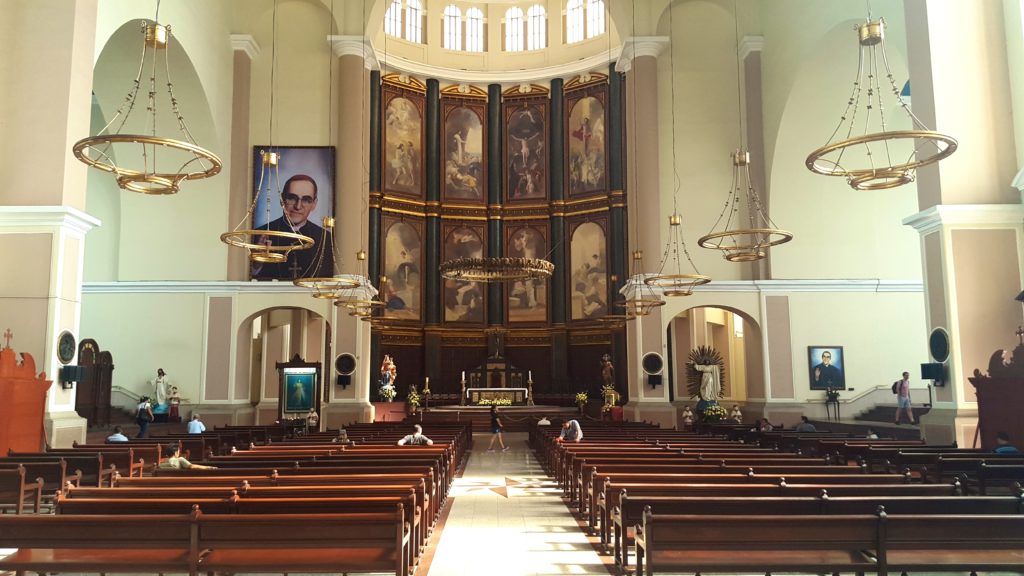

“If they kill me, I will be resurrected in the Salvadoran people,” Romero said shortly before his death. Every Catholic church in our sistering communities has a picture of Romero, and most families have a picture in their homes. Those who knew him speak of him with respect and reverence. Before Oscar Romero was canonized, he was already a saint in the hearts of Salvadorans and many more throughout Latin America.

I have read many of the homilies from his final years. It seems that he never lost hope for peace and justice. He spoke often of the crucified Christ who suffered with his people and knew their wounds. Today, Salvadorans have greater democratic freedoms, but the country suffers from intense gang violence (also linked to U.S. policies). Many youth do not have the opportunity to attend middle or high school let alone college. On the day of his canonization, let us join Saint Oscar Romero in praying for the future of his people, our brothers and sisters in El Salvador.

Above: the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Holy Savior in San Salvador, where St. Romero’s tomb is.